How to Create a CSIRT: 10 Best Practices

Any security practitioner will tell you that incident response is arguably the most important thing they will ever have to do. It’s important to plan, however, which means mapping out roles and responsibilities. Organizations should also decide how and when critical communication should occur and think through when or if to bring in external people — for example, legal counsel, law enforcement or forensic specialists.

These steps are all critical. But getting started on that planning, making sure all these steps are defined and accounted for ahead of time, can be a challenge. Your team won’t know whether its presuppositions about what it would need were correct until there’s an actual event. Plus, it’s hard to find practical advice on this topic. That isn’t to say advice doesn’t exist — to the contrary, there’s so much guidance that distilling it into practical steps can prove difficult.

Let’s look at practical steps to take today to ensure your incident response team is appropriately staffed and includes the right stakeholders. With a number of things to pay attention to, incident response team staffing is one of the first things you’ll need to make decisions about: what people you need, who you have available and how best to empower them.

Why you need a CSIRT

Any response effort requires a computer security incident response team (CSIRT) with different skills. No single individual or functional area — no matter how well-intentioned — can do it all.

Teams need to be empowered to take action. You may need to rapidly decide whether and how to spend money — on external specialists, for example — to bring in law enforcement, to inform the media or to implement specific technical measures. Being empowered means bringing in stakeholders instrumental to those decisions and the decision-makers who can funnel them into actions. Consider the decision to bring in law enforcement: Spending two weeks tracking down someone in the legal department to make a decision about whether or when to do so eats into time you won’t have during an incident — particularly when a disclosure clock might be ticking. Having those people involved from the beginning, or mapping a path to reach them rapidly, is important.

Also consider the diversity of skills. The only thing you can predict about an incident before it happens is that you won’t be able to predict it. Because each incident is different, you won’t know what skills you’ll need during an incident until it happens. Consequently, having a diverse skill base to begin with — and being empowered to rapidly bring in folks with different skills when you need to — is prudent.

Best practices for creating a CSIRT

A variety of personnel and skills are needed during an incident. But how do you organize them? And how do you prepare to gain access to them ahead of time?

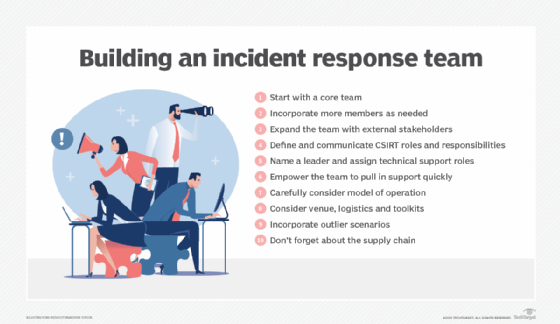

For help in building a CSIRT in your organization, follow these 10 best practices.

1. Start with a core team

Start with a small, nimble group of stakeholders as the core team. This core group represents the individuals in the organization with direct responsibility for managing the incident as it unfolds.

A small, empowered team of CSIRT members can be more agile and respond faster than a large, bulky committee. It can also make decisions quickly and communicate fast-moving updates rapidly, while a larger group takes longer to get resources marshalled and everyone on the same page.

While it’s by no means a universal requirement, a good organizing principle is to maintain a small, nimble team at the core and establish external connections to other groups for times when additional skills, stakeholders and decision-makers are necessary.

2. Incorporate more members as needed

There are no hard and fast rules about who to involve. Your organization’s line of work, business culture and internal structure will heavily influence personnel choice. A healthcare company, for example, might include representation from IT and clinical environments since clinical systems — such as biomedical devices and imaging modalities — might be affected differently by attacks, have different cybersecurity requirements and require different skills to remediate and do further investigative activity. By contrast, a broadcasting company might include specific groups that oversee the broadcast network, while an electric utility might include engineers responsible for industrial control systems.

Functional members of the team will vary based on the technology landscape, overall organizational model or hierarchy, business context, risk landscape, corporate culture and any other relevant factors about the organization.

3. Expand the team with external stakeholders

Think through which relevant external groups to include beyond the core team. Section 2.4.4, “Dependencies within Organizations,” in NIST’s Computer Security Incident Handling Guide provides a good starting point for thinking through what those external stakeholders might be. It recommends incorporating management and executives, IT support, information security, legal, human resources, media relations, business continuity and disaster recovery teams and physical security and facilities personnel. Include other groups based on your organization’s needs.

You can use two approaches to bring others into the team. One is to include representation from other teams directly on the core team. The advantage is that, throughout the entirety of the incident, appropriate representation is within arm’s reach, should it be needed, and directly looped into all the phases of the response activity. The downside is that, the more people on the core team, the more unwieldy activities can become, and more organization may be required to ensure things run smoothly. Also, the more people involved, the more difficult it can be — should it be required — to sequester or contain information about the incident.

An alternative is to define pathways of reporting and communication to enable quick consultations with those who need to stay informed and to speed up decision-making. This approach also helps unlock resources, so the right skills are available when needed.

4. Define and communicate CSIRT roles and responsibilities

Address the internal organization of the team itself and who among the core team members and cross-functional team relationships are responsible for what. Keep in mind that a lot of different things need to happen during an actual event. You’ll need the following:

- Decision-makers.

- Technical staff to gather additional data and research issues.

- People to communicate to other teams, to management and, in some cases, externally to law enforcement, the press, customers, business partners and others.

- People to connect with outside parties and carry out numerous other key activities.

Define these responsibilities ahead of time and create an agreed-upon responsibility assignment matrix. Doing this formally, collectively, collaboratively and in writing is beneficial. Keep in mind that some time may elapse between when you prepare the plan and when it’s used as the playbook for a real event. Having the formal artifact reminds participants of their responsibilities and ensures there’s no ambiguity about who’s doing what.

5. Name a leader and assign technical support roles

As responsibilities are assigned, decide who is leading the group. Define a single point of accountability — such as a CSIRT manager or team leader — ahead of time to help avoid friction during an actual incident.

This leadership role provides an unambiguous point of contact to executives, enables rapid decision-making and gives everyone a clear and well-understood arbiter of disputes. Likewise, having appropriate technical staff — both those with the skill sets to understand the technology, applications and environments in the organization and those who can research the threats, tradecraft, attacks and indicators of compromise — is important.

6. Empower the team to pull in support quickly

Have a streamlined and easy-to-navigate process to pull in new resources, such as technical subject matter experts, as needed. During an incident you may discover you need new skills not available on the core team or even available in-house. The team may lack a required specialist, for example, in a certain application or system tool, in forensics, in reverse-engineering specific malware or in some other key area.

The team needs to be able to rapidly tap the necessary personnel, drawing from other teams within the organization or from consultants or external specialists. To support this, the team must be able to communicate with the rest of the organization to locate the necessary resources and get quick access when needed.

For skills not available in-house, figure out how to budget for, contract and incorporate people with those skills before an incident occurs. Think through possible relationships with external parties — such as consulting teams, managed security service providers (MSSPs) and forensic specialists — so they can be brought to bear with minimal lag time when needed.

7. Carefully consider model of operation

Once you have an idea of who is involved, think through is how to enable the team most effectively — in other words, what resources will be available to the team when the time comes. Planning ahead lets you optimize the team to be maximally effective during an incident. You can’t plan for everything, of course, but making fewer decisions in the heat of the moment will help streamline the team’s operations.

Start by considering the model of operation. Will the team only be called together under certain conditions — for example, when an incident is officially declared? Or will it exist in some form — either fully or partially staffed — at all times? Some organizations might choose to maintain resources within a security operations center (SOC), while others might employ a computer emergency response team (CERT) or CSIRT model.

What’s the difference between SOC, CERT and CSIRT? A SOC is a consolidation of security operations responsibility under one umbrella that can be centralized or virtual and distributed. The role of the SOC can include incident response, but it usually includes other security operations as well — for example, security monitoring, vulnerability scanning, forensics and other key security efforts. The SOC might oversee multiple different environments — such as cloud environments, on-premises networks, data centers or any other relevant environment — within the organization.

CSIRT or CERT models, by contrast, focus specifically on responding to incidents. These can operate as part of the SOC, if there is one, or exist independently. They can be spun up in an ad hoc fashion — pulled together from various resources to respond to a particular event — or exist as a fully staffed, separate, permanent operational group. Which operating model you choose will depend on the size of your organization and its business context.

8. Consider venue, logistics and toolkits

Think through how the CSIRT staff will function. How and where will it meet? Are participants all in one location, or are they geographically distributed? What tools will they have access to, and how will they communicate and collaborate?

These decisions will intersect with the organizational model you employ. A team that exists as part of a broader SOC, for example, might be able to use existing dedicated space and prefer in-person, physical meetings. It might use tools and software the SOC already has access to as the backbone of its workflow — for example, using existing ticketing and workflow tools. An ad hoc CSIRT, where team members are all in one place, might choose to carve out a war room in the facility where those team members reside. A geographically distributed CSIRT might prefer to communicate primarily via collaboration tools such as Slack, Zoom, Microsoft Teams or purpose-built incident response collaboration tools.

Don’t get hung up on the specifics of the right way to organize, operate or communicate. Instead, think it through ahead of time in a systematic, workmanlike way so you don’t run into surprises in the middle of a critical event. Consider what organizational model and communication methods make the most sense, given the number of personnel involved, the context and budget available, the needs of the organization and the threat landscape, among other factors.

9. Incorporate outlier scenarios

You can’t always assume that connectivity, communications and existing tools will work as expected during an incident. Severe outage can often happen contemporaneously with issues or outages affecting internal or external connectivity that disenable team members from communicating or prevent staff from using existing tools.

For these situations, consider alternate communication channels and strategies to help the team get their work done without access to critical applications such as Slack, Teams, email or VoIP. The specifics of what to do here vary according to organizational model and other contextual factors. A distributed team, for example, might issue team members satellite communications as a backup if an incident affects cellular or primary internet communications. Your organization’s decision will depend on factors including internal organization, the staffing model and goals.

Which scenarios should be included? As a general rule, if a dependency exists, think through and prepare guidance around how the team will function if that dependency is unavailable.

10. Don’t forget about the supply chain

Most organizations have some capabilities, tools, services and environments delivered by personnel who do not work within their organization. This can include those with a direct role to play in the identification, vetting and resolution of an incident, such as managed detection and response, managed endpoint detection and response or managed extended detection and response providers and MSSPs. It can also include those with shared responsibility for specific aspects of the environment, such as cloud providers, vendors or partners that provide capabilities essential to performing work.

Think through these relationships when creating a CSIRT. Depending on the vendor and what it does, plan what to do in the event that the third party is unavailable. This is particularly important when the vendor in question is responsible for a critical piece of the incident response equation.

Thinking these things through ahead of time saves time, frustration and risk down the road. Put in the work to make sure you’re doing what makes the most sense for you and your organization.