What is a virus (computer virus)?

What is a virus (computer virus)?

A computer virus is a type of malware that attaches itself to a program or file. A virus can replicate and spread across an infected system and it often propagates to other systems, much like a biological virus spreads from host to host. Once a virus has infected a system, it can attach to other programs or documents, modify or destroy them, or control how the computer or other devices behave.

Viruses require human intervention to spread. Attackers will intentionally place the virus in harm’s way and then leave it up to end-users to carry out the actions necessary to infect their own systems. For example, cybercriminals might set up malicious websites or conduct email campaigns that attach viruses to their messages.

Once the traps are set, users can easily infect their own systems by opening email attachments, downloading executable files, visiting websites or clicking on web advertisements (malvertising). If any such sources are hiding a virus, the user’s computer will often become infected. Viruses can also spread through infected removable storage devices, such as USB flash drives.

Computers are also susceptible to other types of malware such as computer worms. Unlike a virus, a worm is a standalone program that can spread without human interaction. Other types of malware include spyware, ransomware and trojans. In some cases, viruses are used in conjunction with other types of malware. For example, cybercriminals might use a virus to gain the system foothold they need and from there carry out a ransomware attack.

Once a virus has infiltrated a computer, it can infect other system software or resources, modify or disable core functions or applications, or copy, delete or encrypt data. Some viruses begin replicating as soon as they infect the host, while other viruses lie dormant until a specific trigger causes the device or system to execute malicious code. A virus replicates by creating its own files and attaching to legitimate programs or documents. It can even infect the computer’s boot process.

Many viruses include evasion or obfuscation capabilities designed to bypass modern antivirus and antimalware software and other security defenses. The rise of polymorphic malware, which can dynamically change its code as it spreads, has made viruses more difficult to detect and identify.

How does a computer virus spread?

Viruses use multiple techniques to spread between systems, a process known as virus propagation. Typically, a virus can spread from one system to another only if a user takes some type of action. For example, if a virus is attached to an executable file, a user might download the file from the internet, receive it in an email message or copy it from a removable storage device. As soon as the user executes that file, the virus springs into action, running malicious code that infects the user’s system.

Some viruses might include complex mechanisms for spreading to other systems. For instance, a virus might copy itself to a computer’s removable media or shared file servers on the network. A virus might also be able to attach itself to outgoing email messages. Regardless of how it’s done, its goal is to propagate the infection across the network and onto other systems.

In such cases, the lines become blurred between viruses, which require human assistance to spread, and worms, which spread on their own by exploiting vulnerabilities. The key difference is that the virus will always require a user to take an action that causes the initial infection. A worm does not require such intervention.

Viruses can also spread between systems without writing data to disk, making it more difficult for virus protection and removal products to detect them. These fileless viruses are often launched when a user visits an infected website and unknowingly downloads the virus. The virus exists completely within the computer’s system memory, running its malicious payload and then disappearing without a trace.

What does a virus do to a computer?

Virus propagation is only half the equation. Once the virus gains a foothold on the infected system, it carries out whatever exploit it was designed to perform, a process referred to as payload delivery. This is when the virus attacks the target system.

After infecting a system, a virus might be able to carry out almost any operations, depending on its capabilities and level of access. Access is usually determined by the privileges granted to the user who took the action that caused the infection. This is one of the main reasons that security professionals encourage organizations to follow the principle of least privilege (POLP) and not grant users administrative rights on their own systems. Administrative privileges can provide a virus with unlimited access.

Cybersecurity principles are often referred to as the CIA triad, which stands for confidentiality, integrity and availability. A virus’s payload can potentially violate one or more of these principles:

- Confidentiality attacks. The virus tries to locate sensitive information stored on the target system and share it with the attacker. For example, the virus might search the local storage drive for passwords, credit card numbers, Social Security numbers or other personally identifiable information and then funnel the information back to the attacker.

- Integrity attacks. The virus tries to modify or delete information stored on the target system. For example, the virus might delete database files or modify configurations of the operating system (OS) to help avoid detection.

- Availability attacks. The virus tries to prevent the legitimate user from accessing the system or the information it contains. For example, a virus might encrypt data stored on the system as part of a ransomware attack. Those responsible for the attack will then demand a ransom payment in exchange for the decryption key.

Cybercriminals might also use a virus to join a system to a botnet, thereby placing it under the attacker’s control. Systems joined to botnets are commonly used to conduct distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks against websites and other systems.

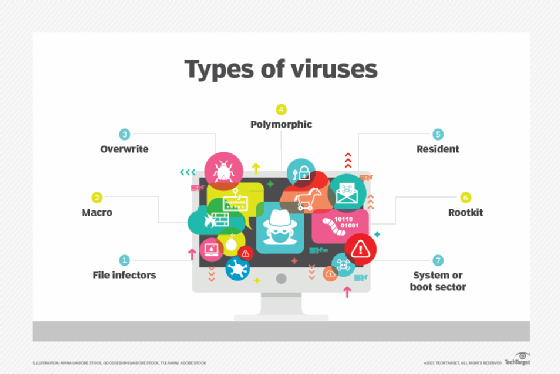

Types of computer viruses

Computer viruses come in many forms and take different approaches to infecting their target systems. Although they have traditionally targeted Windows computers, other systems — including macOS, Linux, iOS and Android devices — are also susceptible. The following types of viruses are among the more common ones to protect against:

File infector viruses. This type of virus is specific to executable files. Some of these viruses attach themselves specifically to selected COM or EXE files. Others can infect any program for which execution is requested, including SYS, OVL, PRG and MNU files. When the infected program loads, the virus loads also. Other file infector viruses arrive as wholly contained programs or scripts sent as an attachment to an email or text message.

Macro viruses. These viruses specifically target macro language commands in applications such as Microsoft Word. In Word, a macro is a saved sequence of commands or keystrokes that is embedded in the documents. Macro viruses, or scripting viruses, can add their malicious code to the legitimate macro sequences in a Word file. Microsoft disabled macros by default in more recent Word versions. As a result, hackers have turned to social engineering schemes to convince targeted users to enable macros and launch the virus.

Overwrite viruses. This type of virus is designed specifically to destroy a file or application’s data. After infecting a system, the virus begins overwriting files with its own code. These viruses can target specific files or applications or systematically overwrite all files on an infected device. An overwrite virus might also add code to files or applications to cause them to spread the virus to other files, applications or systems.

Polymorphic viruses. A polymorphic virus is a type of malware that can change or apply updates to its underlying code without changing its basic functions or features. This process helps a virus evade detection from antimalware and threat detection products that rely on virus signatures. Even if a security product can identify a polymorphic virus by its signature, the virus can alter itself so it cannot be detected.

Resident viruses. This type of virus embeds itself in the computer’s system memory, after which, the original virus is no longer needed to spread the infection. Even if the original virus is deleted, the version stored in memory can be activated when the OS loads a specific application or service. Resident viruses are problematic because they can evade antivirus and antimalware software by hiding in memory.

Rootkit viruses. A rootkit virus is a type of malware that installs an unauthorized rootkit on an infected system, giving attackers full control of the system, including the ability to modify or disable functions and programs. Rootkit viruses were designed to bypass traditional antivirus software that scanned only applications and files. More recent versions of major antivirus and antimalware programs include rootkit scanning to identify and mitigate these types of viruses.

Boot sector viruses. This type of virus infects executable code found in certain system areas on a disk. The virus might infect the system’s boot partition, the disk’s master boot record (MBR), or its disk OS (DOS) boot sector. In a typical attack, the target computer is infected by files on an external storage device. Rebooting the system will trigger the virus, which then modifies or even replaces the existing boot code. When the system is booted next, the virus will be loaded and immediately run. Boot viruses are not as common now because today’s devices rely less on DOS instructions.

How do you prevent computer viruses?

Here are some steps that can help you prevent a virus infection:

- Install current antimalware software and keep the software and definitions up to date.

- Use the antimalware software to run daily scans.

- Disable autorun to prevent viruses from propagating to media connected to the system.

- Regularly patch the OS and applications installed on the computer.

- Don’t click web links or open attachments in email from unknown senders.

- Don’t download files from the internet from unknown senders or untrustworthy sites.

- Install a hardware-based firewall.

What are signs you might be infected with a computer virus?

Certain behaviors might indicate your computer has been infected:

- The computer takes a long time to start up or performance is slow or unpredictable.

- The computer frequently crashes or generates error messages.

- The computer and its applications behave erratically, such as not responding to clicks or opening files on its own.

- If the computer has a hard disk drive (HDD), it constantly spins or makes noise.

- Email messages are corrupted or mass emails are being sent from your account.

- Pop-up messages or adware constantly interrupt the user.

- The computer’s available storage is unexpectedly reduced.

- Files and other data on the computer have gone missing.

How do you remove a computer virus?

In the event a computer becomes infected, the user or an administrator might try these steps to remove it:

- Reboot the computer into safe mode. The process of accessing safe mode will depend on the OS version.

- Delete temporary files. Where possible, use tools available in safe mode such as the Disk Cleanup utility in Windows.

- Download an on-demand virus scanner and a real-time virus scanner.

- Run the on-demand scanner and then the real-time scanner. Ideally, this will remove the virus.

- Reinstall any damaged files or programs.

If the on-demand and real-time virus scanners fail to remove the virus, the virus might require manual removal. For this, turn to an expert who knows how to view and delete system and program files in the target environment.

History of computer viruses

Robert Thomas, an engineer at BBN Technologies, developed the first known computer virus in 1971. Known as the Creeper virus, the experimental program infected mainframes on the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET). The virus displayed the teletype message: “I’m the creeper: Catch me if you can.”

The first computer virus to be discovered in the wild was Elk Cloner. The virus infected Apple II computers through floppy disks and displayed a humorous message. Richard Skrenta developed Elk Cloner in 1982. The 15-year-old designed it as a prank, but it demonstrated how a potentially malicious program could be installed in an Apple computer’s memory and prevent users from removing the program.

The term computer virus emerged a year later. Fred Cohen, a graduate student at the University of Southern California (USC), wrote an academic paper titled “Computer Viruses — Theory and Experiments.” He credited his academic advisor and RSA Security co-founder Leonard Adleman with coining the term in 1983.

Famous computer viruses

Since their inception, viruses have been infecting computers belonging to individuals, businesses, governments, and other organizations. Notable examples of early computer viruses include the following:

- Brain virus. The virus initially appeared in 1986 and is considered the first Microsoft DOS (MS-DOS) PC virus. BA boot sector virus, Brain spread through infected floppy disks. Once it infected a new PC, the virus would install itself to the system’s memory and subsequently infect any new disks inserted into that PC.

- Jerusalem virus. Also known as the Friday the 13th virus, the Jerusalem virus was discovered in 1987 and spread throughout Israel via floppy disks and email attachments. The DOS virus would infect a system and delete all files and programs when the system’s calendar reached Friday the 13th.

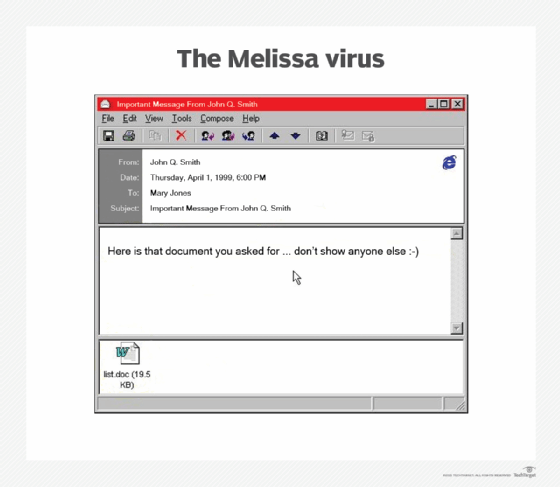

- Melissa virus. Having first appeared in 1999, the virus was distributed as an email attachment. If Microsoft Outlook was installed on the infected system, the virus would be sent to the first 50 people in the user’s contact list. The Melissa virus also affected macros in Microsoft Word and disabled or lowered security protections in the program.

- Archiveus Trojan. Having debuted in 2006, the virus was the first known case of ransomware. It used strong encryption to encrypt the users’ files and data. Archiveus targeted Windows systems and demanded victims purchase products from an online pharmacy. The virus used Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA) encryption algorithms, while other ransomware used weaker, easily defeated encryption technology.

- Zeus Trojan (Zbot). The virus was one of the most well-known, widely spread viruses in history. First seen in 2006, it evolved over the years, with new variants still emerging. The Zeus Trojan was initially used to infect Windows systems and harvest banking credentials and account information from victims. The virus spreads through phishing attacks, drive-by downloads and man-in-the-browser attacks. Cybercriminals adapted the Zeus malware kit to include new functionality to evade antivirus programs and spawn new variants, such as ZeusVM, which uses steganography techniques to hide its data.

- Cabir virus. This was the first verified example of a mobile phone virus. It showed up in the now-defunct Nokia Symbian OS. The virus was attributed to a group from the Czech Republic and Slovakia called 29A. The group sent the virus to several security software companies, including Symantec in the U.S. and Kaspersky Lab in Russia. Cabir is considered a proof-of-concept (POC) virus because it proves that a virus can be written for mobile phones, something that was once doubted.

Learn about 12 common types of malware attacks and how to prevent them and how to avoid malware on Linux systems. Explore the top types of information security threats for IT teams and ways to prevent computer security threats from insiders.