What is personally identifiable information (PII)?| Definition from TechTarget

What is personally identifiable information (PII)?

Personally identifiable information (PII) is any data that could potentially identify a specific individual.

Any information that can be used to distinguish one person from another and can be used to de-anonymize previously anonymous data is considered PII.

PII might be used alone or in tandem with other relevant data to identify an individual and can incorporate direct identifiers that can identify a person uniquely, such as passport information, or quasi-identifiers that can be combined to successfully recognize an individual, such as race or date of birth.

Why does PII need to be secured?

Stolen data containing PII can result in extensive harm to individuals. Protecting PII is essential for personal privacy, data privacy, data protection, information privacy and information security. With just a few bits of an individual’s personal information, thieves can create false accounts in the person’s name, incur debt, create a falsified passport or sell a person’s identity to a criminal.

As individuals’ personal data is recorded, tracked and used daily — such as in biometric scans with fingerprints and facial recognition systems used to unlock devices — it is increasingly essential to protect individuals’ identities and any pieces of identifying information unique to them.

What is considered PII?

Any information that can uniquely identify people as individuals, separate from all others, is PII. This includes information that can directly identify an individual, or information that, if linked to other information, can identify an individual. These are called direct identifiers and quasi-identifiers, respectively.

Direct identifiers include the following:

- Address.

- Biometrics such as fingerprints.

- Credit or debit card number.

- Driver’s license number.

- Email.

- Name.

- Social Security number (SSN).

- Telephone number.

Quasi-identifiers include the following:

- Age.

- Date of birth.

- Gender.

- Geographic data.

- Passport number.

- Race.

Definitions for PII vary. The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) states, “It is important for an agency to recognize that non-PII can become PII whenever additional information is made publicly available — in any medium and from any source — that, when combined with other available information, could be used to identify an individual.”

Although the legal definition of PII may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and state to state, the term typically refers to information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual’s identity, either by itself or in combination with other personal or identifying information that is linked or linkable to an individual.

The Department of Energy (DOE) defines PII as follows: “Any information collected or maintained by the department about an individual, including but not limited to education, financial transactions, medical history and criminal or employment history, and information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual’s identity, such as his/her name, SSN, date and place of birth, mother’s maiden name, biometric data and including any other personal information that is linked or linkable to a specific individual.”

This information includes more examples of what can be considered PPI and can be more sensitive depending on the degree of harm, embarrassment or inconvenience it will cause an individual or organization “if that information is lost, compromised or disclosed,” according to the DOE.

Sensitive vs. nonsensitive PII

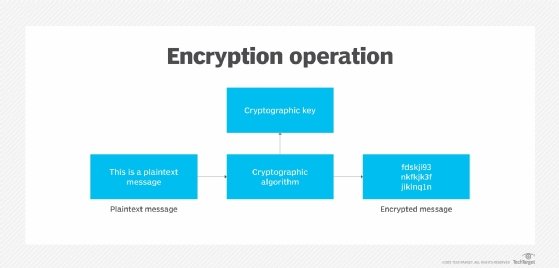

PII can be labeled sensitive or nonsensitive. Nonsensitive PII is information that can be transmitted in an unencrypted form without resulting in harm to the individual. Nonsensitive PII can be easily gathered from public records, phone books, corporate directories and websites. This might include information such as zip code, race, gender, date of birth and religion — information that, by itself, could not be used to discern an individual’s identity.

Sensitive PII is information that, when disclosed, could result in harm to the individual if a data breach occurs. This type of sensitive data often has legal, contractual or ethical requirements for restricted disclosure.

Sensitive PII should, therefore, be encrypted in transit and when data is at rest. Such information includes biometric data, medical information covered by Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), personally identifiable financial information (PIFI) and unique identifiers, such as passport or Social Security numbers.

Also on the list of sensitive PII is the following:

- Bank accounts.

- Credit card numbers.

- Electronic and digital account information, such as email addresses and internet account numbers.

- Employee personnel records.

- Password information.

- School identification numbers.

- Tax information, including SSNs and Employer Identification Numbers (EINs).

How is PII commonly stolen?

Cybercriminals have a number of ways to steal someone’s PII. One of the more common ways is through social engineering attacks like phishing techniques. These methods prey on an individual’s trust and are based on psychological manipulation. Threat actors carry out attacks this way by manipulating and tricking victims into revealing their sensitive information, typically PII, that the attacker can then use to gain access to their system. Attackers might ask for information such as someone’s name, password, SSN or bank account number. Threat actors normally start this method through contact avenues such as emails, SMS messages and phone calls.

For example, an email message could be sent to an organization’s employee that includes a link to a convincing-looking website. That website might then ask for that user’s PII for “authentication” purposes, where, in reality, it is an input that sends the PII to the attacker. The attacker can then use the PII to gain access to the employee’s and the organization’s systems.

Other various ways an attacker can steal PII include gaining access through misconfigured servers, unsecured devices, through physical access, cracking unsafe passwords and man-in-the-middle attacks.

How is PII used in identity theft?

A number of health-related organizations, financial institutions — including banks and credit reporting agencies — and federal agencies, such as the Office of Personnel Management and the Department of Homeland Security, have experienced data breaches that put individuals’ PII at risk, leaving them potentially vulnerable to identity theft.

The kind of information identity thieves are after will change depending on what cybercriminals are trying to gain. By hacking and accessing computers and other digital files, they can open bank accounts or file fraudulent claims with the right stolen information.

In some cases, criminals can open accounts with just an email address. Others require a name, address, date of birth, SSN and more information. Some accounts can even be opened over the phone or on the internet.

Additionally, physical files — such as bills, receipts, physical copies of birth certificates, Social Security cards or lease information — can be stolen if an individual’s home is broken into. Thieves can sell PII for a significant profit. Criminals might use victims’ information without their realizing it. While thieves might not use victims’ credit cards, they can open new, separate accounts using their victims’ information.

PII laws and regulations

As the amount of structured and unstructured data available keeps mushrooming, the number of data breaches and cyberattacks by actors who realize the value of PII continues to climb. As a result, concerns have been raised over how public and private organizations handle sensitive information.

Government agencies and other organizations must have strict policies about collecting PII through the web, customer surveys or user research. Regulatory bodies are hammering out new laws to protect consumer data, while users are looking for more anonymous ways to stay digital.

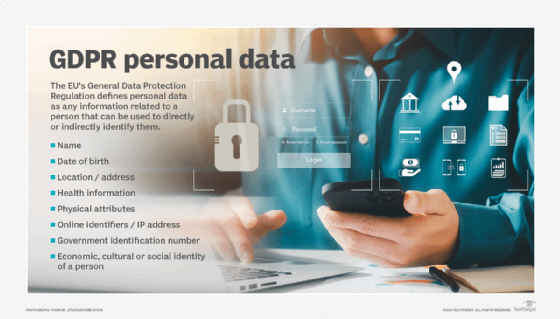

The European Union’s (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is one of a growing number of regulations and privacy laws that affect how organizations conduct business. GDPR, which applies to any organization that collects PII from citizens in the EU, has become a de facto standard worldwide. GDPR holds these organizations fully accountable for protecting PII data, no matter where they might be headquartered.

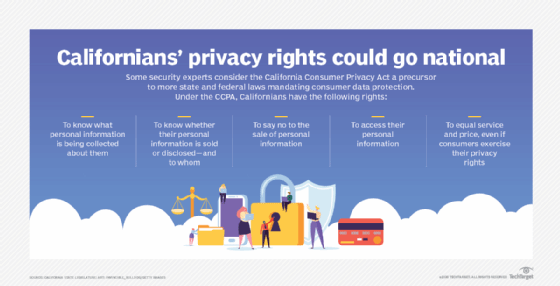

In the United States, different states have different laws regarding PII. For example, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) implements several standards similar to GDPR, such as the ability to request data to be deleted and the ability to opt out of the sale of PII.

PII breaches

There have been many cases where the PII of millions — and in some cases, billions — of customers was leaked. Some of the more well-known incidents involved companies such as Equifax, Meta (previously known as Facebook) and Yahoo.

The 2013 Yahoo data breach exposed the PII of all 3 billion of its users. The data breach was initially discovered during Yahoo’s merger with Verizon, and was not disclosed in its public filings for almost two years. According to Yahoo, stolen user data from the breach could have included names, email addresses, hashed passwords, telephone numbers, birth dates as well as both encrypted and unencrypted security questions and answers.

The 2017 Equifax data breach exposed the PII of up to 147 million people. The initial number of victims was first announced by Equifax to be lower, but over time the credit rating agency admitted to millions of more breaches, adding up to 147 million. The stolen PII included SSNs, birth dates, and addresses. A smaller segment, adding up to 2.4 million consumers, had their names and part of their driver’s license information stolen, but not their home addresses, state of issue for the license or their SSNs. Data forensics experts determined that the attackers were focused on stealing SSNs.

The 2018 Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal exposed the PII of upwards of 87 million Facebook users. The political data analytics firm, Cambridge Analytica, used a legitimate app that was distributed by a third party to collect Facebook user data. The app was willingly downloaded by 270,000 users, but Cambridge Analytica began collecting data from up to 87 million Facebook users. Cambridge Analytica did this to build political profiles of these users with the intention of influencing elections.

The scandal initiated a number of investigations into Facebook’s data-sharing privacy practices, which included an investigation by the Federal Trade Commission. The U.S. Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission also began investigations to determine what Facebook knew about Cambridge Analytica’s activity.

PII security best practices

As organizations continuously collect, store and distribute PII and other sensitive data, employees, administrators and third-party contractors need to understand the repercussions of mishandled data and be held accountable. Predictive analytics and artificial intelligence (AI) are used by organizations to sift through large data sets so that any data stored is compliant with all PII rules.

Additionally, organizations establishing procedures for access control can prevent inadvertent disclosure of PII. Other best practices include using strong encryption, secure passwords, and two-factor (2FA) and multifactor authentication (MFA).

Other recommendations for protecting PII are:

- Encouraging employees to practice good data backup procedures.

- Safely destroying or removing old media with sensitive data.

- Installing software, application and mobile updates.

- Using secure wireless networks rather than public Wi-Fi.

- Using virtual private networks (VPNs).

- Encrypt PII-related data.

- Implement access control.

- Create incident response plans.

- Continuously assess security postures.

To protect PII, individuals should:

- Limit what they share on social media.

- Shred important documents before discarding them.

- Be aware to whom they give their SSNs to.

- Keep their Social Security cards in a safe place.

- Use a different complex password for each account.

Individuals should also make sure to make online purchases or browse financials on HTTPS sites; watch out for shoulder surfing, tailgating or dumpster diving; be careful about uploading sensitive documents to the cloud; and lock devices when not in use.

PII vs. PHI

Protected health information (PHI) includes information used in a medical context that can identify patients, such as name, address, birthday, credit card number, driver’s license and medical records. PHI is a type of PII. Health information is defined as PHI if it meets any of the 18 elements that are identified by HIPAA.

The 18 elements include the following:

- Name.

- Geographical data.

- Data that relates to a patient’s health and identity.

- Phone numbers.

- Fax number.

- Email address.

- SSN.

- Medical record number.

- Health insurance beneficiary numbers.

- Account number.

- License numbers.

- Vehicle identifiers.

- Device serial numbers.

- Digital identifiers.

- IP address.

- Biometrics.

- Photographic images.

- Any other identifying numbers.

Whether companies handle PII or PHI, they should employ records management programs to gain better control of their data by moving it to more intense document management systems and repositories or by disposing of content that’s no longer required.

In the U.S., PHI is subject to strict confidentiality and disclosure requirements that don’t apply to most other industries. While protecting PHI is always legally required, protecting PII is mandated only in some instances. Under HIPAA and revisions to HIPAA made in 2009’s Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, covered entities — such as healthcare providers, insurers and their business associates — are limited in the types of PHI they can collect from individuals, share with other organizations or use in marketing. In addition, organizations must provide PHI to patients if requested, preferably in an electronic PHI (ePHI) format.

PHI is useful to patients and health professionals; it is also valuable to clinical and scientific researchers when anonymized. However, for hackers, PHI offers a wealth of personal consumer information that, when stolen, can be sold elsewhere or even held hostage through ransomware until the victimized healthcare organization sends a payoff.

In instances of a ransomware attack, organizations might have trouble deciding if they should make the ransomware payments. There are a number of reasons not to give in, however, and a number of methods an organization can use to recover from an attack like this. Also, HIPAA requires covered entities to implement appropriate safeguards to protect ePHI throughout its lifecycle. See how to properly dispose of ePHI under HIPAA.