Knowledge management metrics: How to track KM effectiveness

Knowledge management strategies require a lot of time and effort, but the proper metrics can ensure they benefit organizations.

As modern enterprises generate and store massive amounts of data, employees increasingly rely on complex information to do their jobs. This has led to more complex strategies using knowledge management (KM) to help organizations enforce best practices and retain knowledge. These strategies typically include technologies such as knowledge bases and enterprise wikis along with communities of practice — groups of employees who regularly meet to share KM ideas — to encourage knowledge sharing and make information easily accessible to all employees.

However, as author Kimiz Dalkir mentions in her book Knowledge Management in Theory and Practice, Fourth Edition, senior management leaders often require KM teams to make solid business cases for their programs. In other words, KM teams must use metrics and measurement frameworks to demonstrate how KM programs have benefitted or could benefit their organizations. Knowledge managers often struggle to demonstrate KM’s value in large enterprises.

“Costs are unfortunately all too visible, whereas KM benefits tend to be opaque and long-term,” Dalkir wrote.

In Chapter 10, “Evaluating Knowledge Management,” Dalkir explores important metrics for KM programs and suggests knowledge managers first ask themselves the following questions:

- Why are we measuring? Organizations must understand why they want to measure KM, because this can help them clarify their goals for the strategy. Some evaluate KM to determine ROI, whereas others want to track its effects on product innovation.

- What are we measuring? KM teams should choose metrics related to their specific targets and goals to gain actionable insights. For instance, an organization that wants to improve contact center efficiency could measure and aim to reduce first call resolution time by 20% within six months of the KM program’s implementation.

- For whom are we measuring? KM teams must identify who they’re measuring for, because different stakeholders have different interests. For example, program funders typically want to see monetary benefits, whereas employees want to know how KM could affect their daily work experience.

- When are we measuring? KM programs require evaluations at different phases of their lifecycles. Measurements during the preplanning stage yield a baseline. Then, as the program matures, the organization can compare their measurements against the baseline results.

- How are we measuring? Organizations should use a combination of quantitative, qualitative and anecdotal evaluation methods to assess their KM program’s effectiveness. Quantitative methods can include usage metrics from a company intranet, whereas qualitative methods can include insights gleaned from employee interviews. Anecdotes consist of personal stories about how the KM program affected users.

Answering these questions helps knowledge managers craft evaluation strategies that use the right combination of metrics for their stakeholders and ensure a successful KM strategy for their organizations.

In Chapter 10 of Knowledge Management in Practice and Theory, Fourth Edition, Dalkir goes on to explore common KM metrics, including the benchmarking and balanced scorecard methods. Check out the following excerpt to learn more about these KM metrics. Visit the MIT Press page to learn more about the book.

Benchmarking Method

In benchmarking, a company searches for industry-wide best practices that lead to superior performance (Camp, 1989). It usually consists of a study of similar companies to see how things are done and then adapting the methods for their own use. The Hindu proverb “Know the best to become the best” sums up the practice. Benchmarking, the term used in KM, is competitive intelligence, the term favored by information professionals.

Benchmarking as a tactical planning tool originated with Xerox Business Systems in the late 1970s. Japanese affiliates were selling better quality copiers for less than the manufacturing costs of similar products in the United States. Xerox wanted to know why and whether it could emulate them. One of the first experiments in benchmarking was in production logistics (warehousing, picking, packing, and shipping); Xerox Business Services benchmarked L. L. Bean, a clothing manufacturer with one of the best logistics operations in the world.

Benchmarking is a straightforward KM metric that often represents a good starting point. There are two general types of benchmarking: internal benchmarking, which compares units within the same organization (box 10.1) or compares a single unit over different periods, and external benchmarking, which makes a comparison with other companies.

Spendolini (1992) further describes four types of benchmarking:

1. Industry group measurements: The measurement of various facets of your operation and comparing these to similar measurements. Often the measures have little to do with productivity, customer satisfaction, or best practice. Many industry groups publish comparative data privately (for only members of the group or service), publicly, or both.

2. Best practice studies: The studies and lists of what works best. These are useful to benchmarking research, but they are not useful as metrics. What works best for an entity in its specific environment may not work the same way in another environment. These studies can be useful but they are not benchmarks per se. There are books, consultants, and public accounting firms that report internal audit best practices gathered from research and consulting practice.

3. Cooperative benchmarking: The measurement of key production functions of inputs, outputs, and outcomes with the aim of improving them. An internal audit, for example, compares costs per audit hour, time elapsed to distribute final report, and percentage of recommendations accepted. Cooperative benchmarking is done with the assistance of the entity being studied (the benchmark partner). Often the entity chosen as a benchmark is one that has best practices in the area of interest or has won a major national or international quality award. Internal audit departments are increasingly interested in this method. A version of cooperative benchmarking is collaborative benchmarking. In the collaborative method, both entities study each other and work together to improve.

4. Competitive benchmarking: The study and measurement of a competitor without its cooperation for the purpose of process or product quality improvement. The latter is called reverse engineering. A version of competitive benchmarking is a third party studying a group of competitors and sharing the results with all. The third-party consultant is the only one who knows what data belong to which entity (you obviously know your own but not necessarily anyone else’s).

In the long term, benchmarking lacks sufficient value and flexibility, which leads to other measurement tools and techniques eventually being brought in to measure the effectiveness of KM. Benchmarking is essentially a comparison, undertaken with key leaders in the industry, to identify best practices that a company can emulate to improve its organizational effectiveness. Carla O’Dell at the American Productivity and Quality Center (APQC, http://www.apqc.org) pioneered this technique. Companies using benchmarking avoid reinventing the wheel by looking at what has worked and not worked for other companies operating in comparable environments or industrial sectors. Benchmarking can help an organization evolve to higher maturity levels to become a learning organization by identifying where it stands with respect to KM in relation to the competition.

The first step in benchmarking is to identify the short list of companies for the comparison. Recent trends toward globalization suggest international companies should not be automatically excluded from your short list. In the end, it is a subjective decision as to which companies and which criteria you will be benchmarking against. Typical targets include innovation metrics (How fast are new products developed? How much is invested in research and development?), customer loyalty, KM integration, leveraging of information technology, and quality management.

Tiwana (2000) adapted Spendolini’s (1992) key benchmarking steps to arrive at a better fit with KM:

1. Determine what to benchmark: Which knowledge processes, products, services? Why? With what scope?

2. Form a benchmarking team.

3. Select benchmarking short list—which companies will you be benchmarking against?

4. Collect and analyze data.

5. Determine what changes should be made because of the metrics obtained.

6. Repeat to measure progress when an appropriate amount of time has elapsed.

Benchmarking is of greatest value when a company has clearly identified its strategic objectives and has thought long and hard about which best practices might be transferable and effective for it, considering its own KM drivers and constraints.

Balanced Scorecard Method

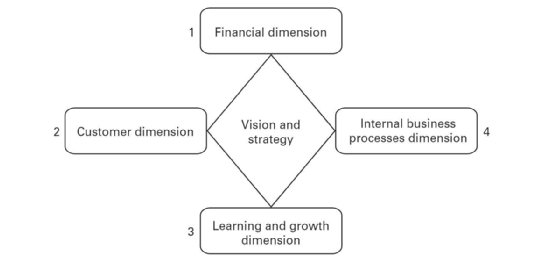

The balanced scorecard method is a measurement and management system that enables organizations to clarify their vision and strategy and translate them into action. It provides feedback on both the internal business processes and the external outcomes to continuously improve strategic performance and results. It is a conceptual framework for translating an organization’s vision into a set of performance indicators distributed along four dimensions: financial, customer, internal business processes, and learning and growth. The “balanced” in the method’s name refers to the balance maintained among the following:

- Long-term and short-term objectives

- Financial and nonfinancial measures

- Internal and external perspectives

- Lagging and leading indicators

- Objective and subjective measures

- Performance results and drivers of future results

Indicators are maintained to measure an organization’s progress toward achieving its vision; other indicators are maintained to measure the long-term drivers of success.

With the balanced scorecard method, an organization monitors both its current performance (e.g., finances, customer satisfaction, and business process results) and its efforts to improve processes, motivate and educate employees, and enhance information systems—its ability to learn and improve. A high-level balanced scorecard is shown in figure 10.2

Variations in the basic design are common. Typical changes include categorization of perspectives (innovation and learning, or employees, in place of learning and growth, for example) and the number of perspectives (adding stakeholders as a separate, fifth perspective, for example). Balance is achieved through the four perspectives, through the decomposition of an organization’s vision into business strategy and then into operations, and through the translation of strategy into the contribution each member of the organization must make to successfully meet its goals.

The financial dimension includes measures such as operating income, return on capital employed, and economic value added. The customer dimension deals with such measures as customer satisfaction, retention, and market share in targeted segments. The internal business process dimension includes measures such as cost, throughput, and quality. The learning and growth dimension addresses measures such as employee satisfaction, retention, and skill sets.

The balanced scorecard metric applies five steps:

1. Translate the KM vision and strategy into measurable goals.

2. Validate these through the establishment of a consensus on the concrete, short-term specific goals.

3. Communicate and link: measure as you go through the objectives and look at how well the reward system is linked to these objectives: are employees trained, motivated, and rewarded to use KM as part of their everyday work?

4. Do a reality check—be sure that you are being detailed enough that you can measure something to assess how well these objectives are being met.

5. Incorporate learning and feedback into your metrics—do a formative and a summative evaluation.

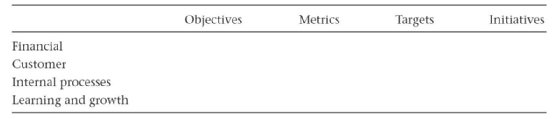

Each dimension of the balanced scorecard can be further expanded to include objectives, metrics, targets, and initiatives, as shown in table 10.1. Objectives are the major goals to be achieved (e.g., profitable growth). Metrics are the parameters that will be monitored to measure progress toward these stated goals (e.g., growth in net margin). Targets are the specific thresholds to be met for each metric (e.g., 2 percent or greater growth in net margin). Finally, initiatives describe the actions, projects, programs, and so on, to be put into place to meet the stated goals.

The balanced scorecard method was originally intended to be a performance improvement metric, but it quickly became apparent that it also serves as an effective strategic management system (Kaplan & Norton, 1992, 1993, 1996). It is applicable to both for-profit and nonprofit organizations and to both private and public sector companies. The balanced scorecard method offers several significant advantages over other approaches, including the translation of abstract goals into action items that can be continuously monitored. It provides objective measures of the current situation and also helps in initiating the changes required to move from the current to the desired future state of the company. The major shortcoming is that it is a much more difficult technique to use than benchmarking. Each balanced scorecard must be developed from scratch because it is customized to individual organizations.

Tim Murphy is an associate site editor for TechTarget’s Customer Experience and Content Management sites.